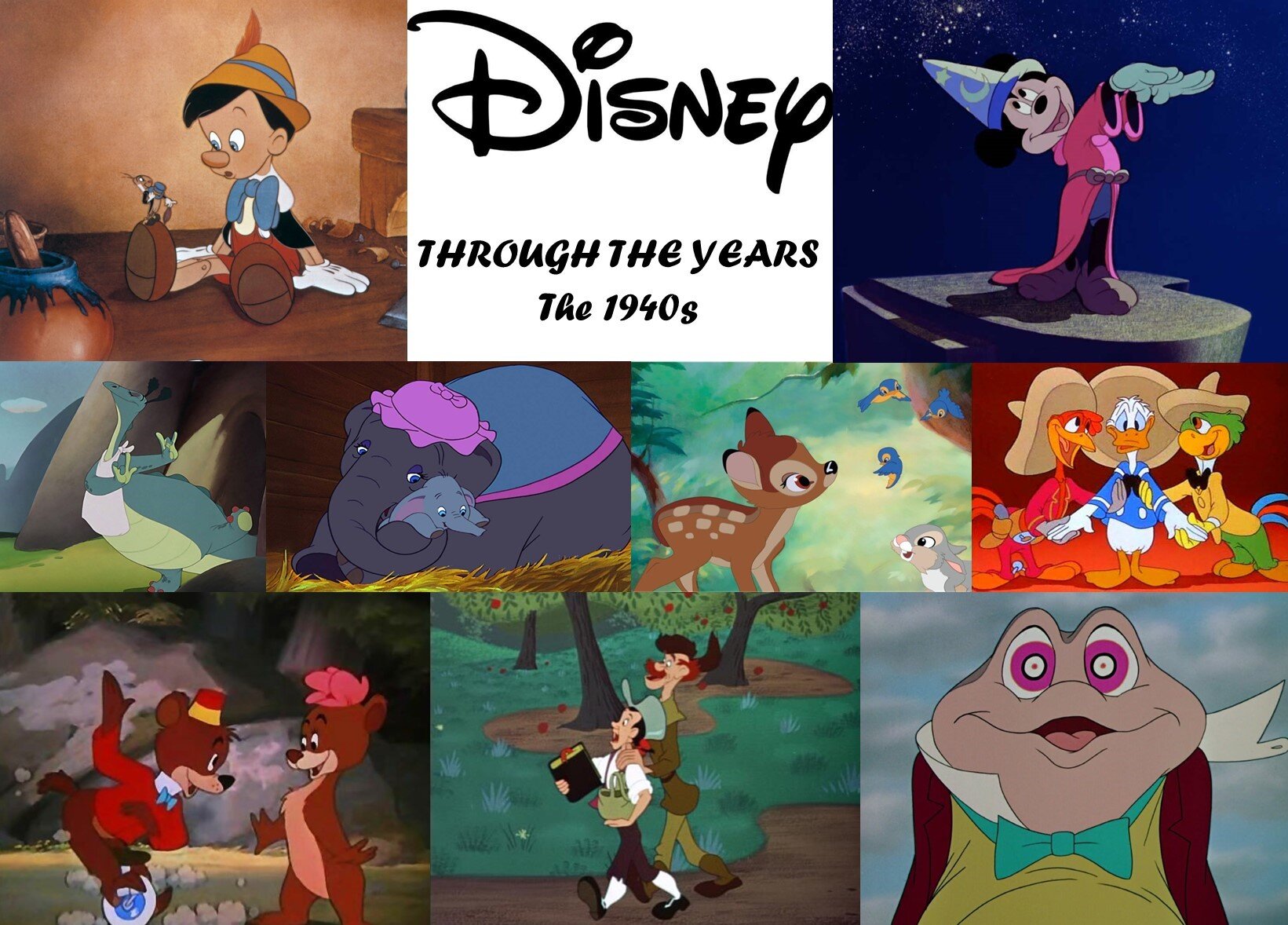

Disney Through the Years: The 1940s

Welcome to the second of many parts to a series of feature articles I’ll be doing in 2021.

Every month this year I am going decade-by-decade through the history of Walt Disney Company’s feature films. I will review each film from Walt Disney Animation Studios and rank them. Starting with the 1950s, I’ll be doing an additional feature in the series that will focus on every live action film by Walt Disney Pictures. So, there will be two features each month. At least, that’s the idea. We are talking as many as 50 movies at a time from a given decade eventually, so… we’ll see if I can keep that twice-monthly schedule.

For more details on what is and isn’t included in this series be sure to check out the first entry that introduces the series.

In this entry, I’ll be reviewing the nine animated movies Disney produced in the 1940s that are available on Disney+. Remember: you can follow along on Disney+ by going to the Search tab and selecting “Disney Through the Years” in the collections below the search bar.

Pinocchio (1940)

Pinocchio was quite the follow-up to 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. Based on the 1883 Italian novel The Adventures of Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi, Pinocchio was a richer experience that pushed the medium forward, provided more fully-realized characters, and was a lot darker than its predecessor.

In Pinocchio, we get Disney’s first set of animal characters and sidekicks. The Italian woodcarver Gepetto has two pets to keep him company: a cat named Figaro and a goldfish named Cleo. Much of the film’s humor comes from Figaro. Jiminy Crickett is the first character we are introduced to and acts as a kind of narrator to the story, as well as the film’s primary character, aside from the titular wooden boy. There’s also a fox named Honest John and his cat sidekick Gideon. And then there’s Monstro, the sperm whale who is introduced in the film’s third act. What’s odd about Pinocchio and its animal characters is there is no consistency in the world-building. Figaro, Cleo, and Monstro are silent and pantomime at most. But Jiminy, Honest John, and Gideon can speak and interact with humans. In the Pleasure Island sequence, where human boys become donkeys and sold to salt mines, most boys are unable to talk anymore while others still retained their human voices through their transformation. But that has some logic to it within the world presented. The fact that the story’s villains Stromboli and the Coachman will do business with a fox and cat is odd, to say the least.

That said, Pinocchio is notable for its contributions to the animated medium. It’s hard to believe that machines, water and other natural elements, and fairy dust were not animated well or at all before Pinocchio. And the film is definitely a step forward from Snow White in its complexity of animated backgrounds, sets, and other objects.

It’s also a darker film in a literal and figurative sense. I don’t think you’re likely to see animated movies as dark as Pinocchio today. In this film you have pre-teens drinking beer and smoking cigars and donkeys referred to as jack-asses. You have terrifying sequences that utilize shadow and partial framing to great effect when characters transform into donkeys, crying out for their mothers. You have a giant whale violently charging at the main characters just because. You have a man who wants to cage and own the main character, separating him from his father forever. You have a handful of amusing moments with Figaro, but practically no joy compared to the seven dwarfs.

And yet, this is a story about navigating the world, letting your conscience help you sort out what is right and wrong, and learning to be honest, brave, and selfless. Pinocchio is a fairy tale about how dark and dangerous and unfair the world can be and how to persevere within it without losing your integrity. And it is one of the most iconic films Disney ever produced: Everyone knows the songs - one of the greatest songbooks in Disney history - everyone knows about the nose that grows with each lie and several quotes like “I’m a real boy!”, everyone recognizes most of the characters and knows exactly what film they’re from. It’s not one of the most pleasant or uplifting of Disney’s films. But it’s certainly one of the most interesting and daring.

Fantasia (1940)

Speaking of daring, we have Fantasia, a film that both pushed the medium forward technically and portended what would dominate the decade: the anthology film. Fantasia is a bit of an experiment that started with a desire to refuel Mickey Mouse’s popularity, which had waned during the 1930s. The Sorcerer’s Apprentice was conceived originally as a short for Mickey, but once the production costs outweighed what the short could earn the idea of including it in a larger feature started brewing. Many classical composers, animators, and music critics were consulted over a 2-year period and what resulted was Fantasia. Fantasia was originally a roadshow with a 15-minute intermission, clocking the film at roughly 2hrs. 20mins. The version you see now is just over 2 hours since most of the intermission was removed (not to mention footage of black centaurs serving white centaurs).

The film is made up of eight pieces with introductions by esteemed music critic and composer Deems Taylor. Taylor is a name largely lost to time in pop culture, but I get the impression he had made a name for himself enough during the early 20th century that he would have been recognizable during the film’s release. Anyway, some of the pieces last a few minutes while others last over 20 minutes. It is the length that the film suffers most from, caused largely by the middle pieces where the film sags: Rite of Spring, which features our planet’s early days and the rise and fall of dinosaurs, and Pastoral Symphony, which features pegusi, fauns, and centaurs celebrating Bacchus, the god of wine. The description of the pieces sound much more interesting than many of the other pieces, but the combination of two of the most forgettable musical pieces in the film and the fairly dull execution of the concepts lead towards a slog of 46 minutes in length.

That said, like in Pinocchio, the animation department was clearly pushing boundaries with animating natural elements and layering, so majority of Fantasia is fascinating and gorgeous. To be sure, Fantasia is full of some unforgettable imagery, too, like the dancing mushrooms and flowers in The Nutcracker Suite, Mickey Mouse in a sorcerer hat fending off the sentient brooms, crocodiles in capes in Dance of the Hours, and the demon Chernabog (a.k.a. Satan) in Night on Bald Mountain.

Fantasia is a legend in animation for good reason. Walt’s dream was to create a series of Fantasia films annually or every few years. I wish he had used the film as a jumping-off point for a series of shorts (The Fantasia Shorts, if you will) that could have continued the legacy in a much more practical manner. Perhaps a couple of the pieces in the original film could have been saved as their own shorts. As is, Fantasia suffers from a sagging middle and a difficult runtime for what it is. A more concise cut could have helped Fantasia hold up as an extraordinary experience.

The Reluctant Dragon (1941)

So, after Pinocchio and Fantasia, Disney took a left turn and released this film, their first live action flick. The plot revolves around radio comedian Robert Benchley going to the Walt Disney Animation Studios in Burbank to pitch a story idea, The Reluctant Dragon, a children’s story his wife adores. That is basically a thin excuse to hang a studio tour on, as Benchley keeps deviating from his escort to an expectant Walt to take a peek at how things operate in the studio. We see the storyboarding, recording, and color processes. In-between we get three animated sequences that take us away from the live action: a storyboarded sequence of Baby Weems, Goofy’s How to Ride a Horse short, and the titular The Reluctant Dragon - with a handful of other animation peppered throughout.

The Reluctant Dragon is one of the studio’s lesser-known works these days. It’s easy to see why. It’s a lark and hardly worthy of serious consideration. The greatest thing one can get out of this is how complicated and pain-staking the process of animation was back in the form’s early days. It gives a certain credence to the perspective that CGI is less impressive or “easy” by comparison. And it is interesting to see maquettes for projects that would soon be delayed until the ‘50s, as well as to see Dumbo or Bambi before the world knew who those characters were. Outside of those perspectives, The Reluctant Dragon is a parenthetical detour for the studio. It was also the only film this decade to earn less than $1 million. Thankfully, the budget was a little over $500,000, so the film managed a profit. But it would be the first film by Disney to fail to measure up to the standards the studio would be remembered for.

Dumbo (1941)

The studio quickly got back on track later that year with this simple tale of a newborn elephant, his mom, and his ears.

Dumbo is a simple film in style, yet is fully balanced emotionally. The film begins with several baby animals being delivered to a circus in Florida. There’s very little dialogue during the first 20 minutes, but so much is communicated and the film is much more delightful than Pinocchio. With his big ears and trusting eyes, Dumbo immediately becomes one of Disney’s most adorable characters. The film touches on parent/child relationships in a very touching way: Mrs. Jumbo has clearly been wanting to have a baby for a long time and is disappointed when everyone around her gets a baby except her. Furthermore, when her baby does arrive via stork, her stork requires a much more complicated process than everyone else’s. It feels like a metaphor for infertility or the challenges some parents have to conceive and birth a child. As such, Mrs. Jumbo is quite protective of her child, which leads her to being judged as “mad”.

That alone adds an interesting layer to the film and leads to one of the most heartbreaking musical sequences in all of Disney lore: ‘Baby Mine’, where child and parent are separated by a cage and reach for each other, longing for the comfort of each other’s “arms”. But what’s more is “Dumbo”, as our protagonist is called by a group of gossiping and bitchy elephants, has unusually large ears. He is shunned by his community for this difference. Timothy Q. Mouse observes all of this and sees no point in it; he accepts Dumbo as he is. This makes Dumbo the film a lovely allegory for the differently-abled and, later, as Dumbo figures out how his differences can make him an interesting attraction, for self-confidence.

I have conflicting feelings about the film’s final 10 minutes. After an absinthe-fueled trip (‘Pink Elephants on Parade’, one of Disney’s biggest WTF?! moments), Dumbo and Timothy are awakened by a murder of crows who poke fun, but eventually give Dumbo a magic feather to hold that “allows” him to fly, leading Dumbo to a greater sense of confidence and a triumphant performance in the end. The problem is the crows are voiced with African American caricatures, led by a white voice actor (Cliff Edwards, a.k.a. Jiminy Crickett). The film’s most famous song, ‘When I See an Elephant Fly’, helps move the story and character development along, but is rooted in minstrel culture. There are offenses and defenses to this sequence that you can read elsewhere. But it does make one question today, “Is this okay?”, which one generally wants to avoid in a final act that is supposed to delight and uplift. On top of that, the end is rushed with bullies barely getting a comeuppance and Mrs. Jumbo’s situation being glossed right over.

However, Dumbo was the studio’s only profitable original film due mostly to low production costs. That said, Dumbo is at least two-thirds an excellent movie and I’m glad Disney+ is acknowledging rather than applying Clearasil to any blemishes in the studio’s past to make them go away.

Bambi (1942)

Bambi may be the first example of the Disney film as we know it. What I mean by that is Bambi feels like a culmination of all of the elements from Snow White, Pinocchio, and Dumbo stirred to perfection. The only element missing from Bambi that we have come to expect from a Disney animated film is a great songbook. Bambi has two musical sequences: ‘Little April Shower’ and ‘Love is a Song’. The latter is completely forgettable despite being nominated for an Oscar for Best Song. The former is a delight, but fails to live up to the best the studio had recorded even at this point.

Regardless, Bambi tells the story of a fawn growing up in the woods. That’s it. There’s not a lot of plot to Bambi, really. Yes, Bambi makes friends in the woods, Bambi learns about the dangers of Man in the meadow, and falls in love. But this film isn’t so much about telling a story, rather providing an experience, spending time with wonderful characters, and reflecting on Man’s effect on nature. Like Dumbo - and to an extent more so - Bambi is absolutely adorable and a delight with the cutest animals ever animated.

What’s interesting is Bambi is generally thought of as a “sad” movie. That’s largely due to a 2nd-act development 40-minutes into the film where Bambi famously loses his mother to Man’s gun. It is a greatly affecting and effective scene, as Bambi, upon reaching safety looks back and claims, “We made it!”. Of course, his mom didn’t make it, which makes that statement of relief heart-breaking. But the film goes on, as life does, to the characters falling in love, surviving a forest fire caused by Man’s presence, and eventually producing their own offspring. Such is the cycle of nature. Bambi provides an experience of nature’s cycle and how Man’s presence perverts that natural order of things. Annual wildfires in North America make Bambi’s events a statement of fact rather than a value judgment pushed on its viewer. It may not sit comfortably with some, but it is what it is.

Regardless, all of this adds up to one of Disney’s greatest films of the 1940s and during Walt’s era overall.

The Three Caballeros (1945)

With World War II cutting off international markets to potential box office grosses, thereby making nearly every release a loss for the studio, and the military occupying part of the studio for propaganda purposes, Disney was forced to make a left turn and steer away from several planned projects. These anthology films would be released annually for the rest of the decade and help make enough money to prevent the studio from going bankrupt and allow it to have a future.

Disney was roped into a Goodwill Neighbor Policy by the State Department before the country even entered the war. The goal was to provide American citizens a better impression of the citizens of its neighboring countries down south. The short film Saludos Amigos and this, The Three Caballeros, were what resulted. The latter also marked the 10th anniversary of Donald Duck, which is why it opens with Donald receiving birthday gifts from his friends in Latin America. The film includes six segments, most of which feature different countries. It isn’t until the third segment, Baia, that the film comes alive. Donald and his Brazilian friend Jose Carioca (introduced in Saludos Amigos) visit the state in Brazil and interact with live action performers. Not only is this segment lively, but it is notable for making The Three Caballeros the first feature film to combine traditional animation with live-action actors. And it works really well!

However, the rest of the film largely devolves into Donald being a horndog chasing after Latina women and a 10-minute finale that is an odd musical fantasia of Donald, live action female performers, and Mexican symbols and flora. It is very weird. And Donald’s birthday celebration ends with his friends Jose and Panchito Pistoles, a Mexican rooster, lighting his ass with fireworks into a multi-lingual ending.

The Three Caballeros is a huge deviation tonally, stylistically, and qualitatively from the groove of animated stories the studio was getting into. But it is still a bit of a technical marvel and manages to dazzle here and there.

Fun and Fancy Free (1947)

After The Three Caballeros, Disney released Make Mine Music and Song of the South. Neither are available on Disney+. Make Mine Music is claimed to be the only Disney Animation Studios film not on the streamer and it’s unclear why. This is the film with the Peter and the Wolf, Casey at the Bat, and Johnnie Fedora and Alice Bluebonnet segments. So, the next film we’ll focus on is this two-part anthology film.

Fun and Fancy Free is a combination of two projects that were considered at one point to be their own features. The two segments are Bongo and Mickey and the Beanstalk. Bongo is about a circus bear who escapes into the wilderness, falls in love with another bear, and fights another bigger bear over her. It was once considered to be a sequel to Dumbo with supporting characters from that film making appearances. That idea was eventually scrapped over time. This segment is a low point for the studio, as it all feels more like an animated short and is never all that interesting or engaging. Dina Shore narrates the story and sings and it’s enough to lull anyone to sleep.

Mickey and the Beanstalk is probably the most well-known of the two, as it was eventually aired during The Wonderful World of Disney in the ‘50s and several times on its own since then. It’s basically an adaptation of the Jack and the Beanstalk story, but with Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and Goofy playing the leads. It’s fairly enjoyable, but far from Disney’s best as it is hurt by narration by a ventriloquist, which isn’t that enjoyable these days.

All in all, Song of the South aside for obvious racist reasons, Fun and Fancy Free is a low point in the decade for Disney Animation Studios, despite performing fairly well at the box office.

Melody Time (1948)

Melody Time is the best of the anthology (or package) films of the mid- to late-’40s (with the possible exception of the unavailable Make Mine Music). It was conceived as a spiritual sequel to Fantasia set to popular music rather than classical. The film is made up of seven segments and all but two - the opening number Once Upon a Wintertime and Trees - are entertaining and memorable. Like the other anthology films, many of the segments were parsed out as cartoon shorts that some are likely to have grown up with instead of as part of this film. The longest of these are The Legend of Johnny Appleseed and Pecos Bill, which are both about American folklore, but it’s also true of Little Toot, an adaptation of a story about a tugboat.

The segment Blame It on the Samba returns to the flavor and characters of The Three Caballeros with Donald Duck and Jose Carioca being cheered up and then blown up by the Aracuan bird via samba music. This segment also adds live action performers to animation. Overall, it certainly wakes the viewer up.

Melody Time fails to hold a candle to what Disney Animation Studios was creating during the first half of the decade, especially its spiritual cousin, Fantasia. And, like the other films released at the time, it still feels like a bunch of cartoon shorts cobbled together. That said, it is one of the best of its kind.

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (1949)

Finally, Disney ended the decade with an anthology of two animated shorts: The Wind in the Willows and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. Like Fun and Fancy Free, these were narrative stories. Unlike Fun and Fancy Free, these are actually engaging.

The first segment, narrated by English actor Basil Rathbone who was best-known as Sherlock Holmes, is an abbreviated, yet fairly accurate adaptation of Kenneth Graham’s The Wind in the Willows. Mr. Toad is a bit more chronically reckless in this version than in the novel, but became a bit of an icon for a few decades and eventually inspired a ride at Disneyland that still exists today.

The second segment became one of Disney’s most popular animated shorts. What’s interesting now is how flawed the story’s hero, Ichabod Crane, was. He pines after the village beauty, but also fantasizes about the riches he’d inherit from her father, a wealthy farmer. Ichabod has a competitor by the name of Brom Bones, undoubtedly the inspiration for Gaston in 1991’s Beauty and the Beast, who also wanted the town’s beauty’s affections. Like The Wind in the Willows, The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is a fairly accurate adaptation of its novel. I’m reminded, however, of Bongo from Fun and Fancy Free in that most of the plot revolves around two characters fighting for the affection of a female character. Sleepy Hollow is a far more entertaining version. What’s interesting about it, though, is it’s best-known for the scene with The Headless Horseman. But that scene makes up the final 10 minutes of the segment and there is only one scene with the Horseman. And I think many forget that it’s suggested that Ichabod died after nearly escaping the Horseman (there is an epilogue that offers the possibility he ran off and lived a happy life elsewhere).

Both segments were eventually parsed out and played on Disney TV programs. Sleepy Hollow became a Halloween staple for Disney and would scare and entertain tots and kids for years. Overall, The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad is the strongest anthology film of the decade, but would still pale in comparison to what Disney Animation Studios proved possible during its first few years.

Thankfully, the last few movies helped the studio earn a profit, so the full feature stories could go back into production and Disney could rebuild the momentum of their early ‘40s work. Plus, Walt Disney dove headlong into live action features in the next decade and began and finished construction of Disneyland. The studio’s future would begin in the ‘50s.

The Ranking

Pinocchio

Bambi

Fantasia

Dumbo

The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad

Melody Time

The Three Caballeros

The Reluctant Dragon

Fun and Fancy Free

What are your thoughts?

Do you like any of the decade’s anthology films?

How would you rank the decade’s movies? Which is your favorite?

Keep an eye out next month for TWO new features as we get into the 1950s with more from the animation studio - plus, Disney starts cranking out the live action adventures! It’ll be The 1950s: The Animated Features and The 1950s: Live Action Features next month!