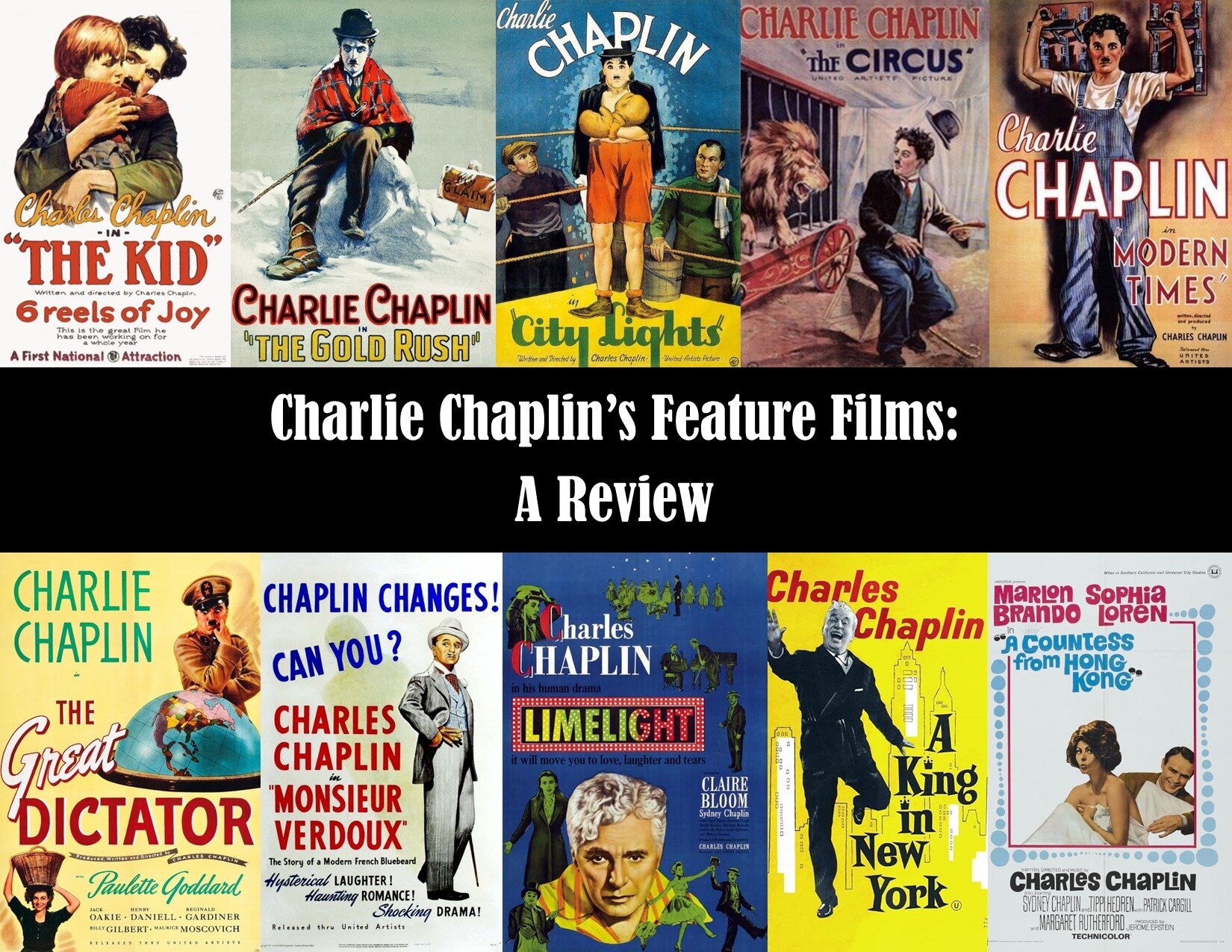

Charlie Chaplin’s Feature Films: A Review

Charlie Chaplin starred in 93 films. He directed 72 of those films. All but 10 of them were short films. That is, depending on who you ask.

If you ask the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences, the American Film Institute, and the British Film Institute, a full-length feature film is any film that exceeds 40 minutes. But if you ask the Screen Actor’s Guild, it is defined as any film that runs a length between 75 and 210 minutes. Well, okay. First of all, if we go by the SAG definition then movies like Dumbo (64 minutes) and several other Disney films, The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (67 mins), or even Lawrence of Arabia (228 mins) or Once Upon a Time in America (240 mins) wouldn’t qualify as feature-length films. Movies like Dumbo would be shorts and epics like Lawrence of Arabia would be… what? Limited series? I don’t know. But the AMPAS, AFI, and BFI standard feels like one that is relevant only in a time when the industry was churning out hundreds of shorts a year that filled movie house schedules rather than today when we watch so much entertainment that runs 45 minutes.

It seems to me the reality is somewhere in-between: roughly 60 minutes or more. Some consider Shoulder Arms (1918) and The Pilgrim (1923) to be among Chaplin’s feature-length films. Both run around 45 minutes long, just over 10 minutes longer than films like A Dog’s Life (1918). For the purpose of this piece, we will be considering Chaplin’s 10 full-length feature films that ran no less than 68 minutes long. I will review each one and then rank them from best to worst. If you haven’t yet seen any of Chaplin’s films then let this serve as an introduction. Most of these films are available to rent on Amazon or stream on Criterion Channel.

The Kid (1921)

At 68 minutes, The Kid is considered by many to be Chaplin’s first full-length feature film. A story about a street Tramp (Chaplin) taking on and raising a little boy (Jackie Coogan), only to have officials question his legitimacy as a parent, this beautiful and often funny film has the hallmarks of what we’d expect from most of Chaplin’s oeuvre:

The mustachioed Tramp as the central character

Physical and situational comedy

Social commentary

The moment when the titular child and the Tramp embrace after a chase over the rooftops has to be one of the most moving moments in all of cinema. If not for an odd dream sequence with angels and demons that seems to accomplish little more than to ensure the film’s feature length, this would be a perfect film. Chaplin had recently lost a newborn child when starting work on this film, so The Kid has a certain heart-breaking ache to it that is absolutely beautiful.

The Gold Rush (1925)

Chaplin made a few short films, most notably The Pilgrim, in-between The Kid and The Gold Rush. Here, Chaplin makes his longest silent film (95 minutes) with a story about The Tramp getting caught up with a couple of men and a love interest while mostly residing in a shack in the snowy Yukon. This is most likely one of the first films of Chaplin’s that features some of the iconic imagery people think of when they think of Chaplin films: eating a shoe, the bread roll dance, the shack teetering over a cliff with its occupants frantically skittering (or sliding) from one side of the shack to another. This film is full of classic gags, which also includes one of its main characters appearing to another, delusional with hunger, as a giant chicken. The comic rapport between Chaplin and Mack Swain, who plays Big Jim, in those scenes in the shack are nearly a non-stop delight and help make the film the classic it is.

Georgia Hale, who pretty much got her big break with this film, but was unable to transition into talkies, plays the love interest. This is the first romantic interest in a Chaplin full feature. Her scenes - and the subplot involving her character and relationship with the Tramp - are, unfortunately, the least interesting in the entire film and weigh down what is otherwise a thoroughly enjoyable film. Anytime her character shows up, you just want to get back to the main plot between the men in the shack. Chaplin would get better at writing love stories - and casting love interests - later on.

The Circus (1928)

The Circus is not one of Chaplin’s better-known films. In fact, it rarely gets a mention in most discussions about Chaplin, as The Gold Rush, City Lights, Modern Times, and The Great Dictator tend to dominate people’s memories. However, The Circus just might be Chaplin’s most hilarious film. With moments like the disappearing act chase, the Tramp as automaton that clocks someone on the head, the circus act try-outs, the caged lion, and the monkeys on high-wire, The Circus may have the highest laugh-per-minute quotient of any of Chaplin’s films. It also has underlying commentary about performance and Chaplin’s line of work as an entertainer. It is certainly worthy of rediscovery.

City Lights (1931)

The Tramp is mistaken by a beautiful blind florist as a rich man. The Tramp, absolutely smitten by her, endeavors several attempts to raise enough money to pay for a cure for her sight. Meanwhile, The Tramp happens to befriend a drunken man of means. City Lights is one of Chaplin’s most beloved films. It has appeared on several ‘Best of’ lists, including the canonical Sight & Sound poll. What’s interesting is this film furthers what Chaplin started with The Kid in the sense of mixing physical and situational comedy with social commentary. In City Lights, the Tramp’s presence always disrupts propriety and the film is full of moments that stick it to rich snobs and politicians. It is worth noting that the greatest gesture of genuine generosity in a story set during the Great Depression comes from a little tramp and not any of the characters with actual means to make a difference in someone’s life.

It is here that Chaplin has his first successful love interest (there is none really in The Circus). Virginia Cherrill, another discovery who made it big in a Chaplin film only to have a short career afterward (she would marry The Earl of Jersey and retire), plays The Blind Girl. While her presence is largely limited, she is lovely and unforgettable. This is often considered Chaplin’s greatest romantic comedy and it is pretty much perfect with one of cinema’s greatest final shots.

And that score! Chaplin always scored his own feature films. The score to City Lights is certainly one of the greatest of all time. Is it Chaplin’s greatest?

Modern Times (1936)

With Modern Times we are deep into the first decade of the talkies. Chaplin poked a little fun at sound by having city officials squawk in the beginning of City Lights. Here, he leaves the talking to the head of a giant corporation. When the Tramp does speak for the first time on film, it’s to sing a series of nonsensical babble, a sort of middle finger to anyone who pressured and anticipated the Tramp to transition into sound. It’s one of Chaplin’s most brilliant moments in his career. The film, a story about the Tramp and a love interest (Paulette Goddard) struggling to get by in a modern world, is Chaplin’s masterpiece. It is here that all of the elements Chaplin had been playing with - physical and situational comedy, social commentary, and love story - came together perfectly. Modern Times features the most iconic image of Chaplin’s filmography: the Tramp stopped in-between gears, pausing to adjust a couple of bolts. It is a blend of man and machine through comedic happenstance and with full comedic affect.

The entire film is full of similar imagery: the dissolve from sheep to a crowd of men going to work, the production conveyer, the food machine trial run… The film is a reaction to the development of sound in film, a technological step forward in the industry. Chaplin was out to prove that a film could be funny, a lead character could still be funny, without the use of sound and talking so much. It also is a reaction to the Great Depression with the Tramp and the Gamin, his love interest, living and getting by in a department store or small house…. Paulette Godard would be one of Chaplin’s greatest leading ladies - and most successful, starring in 1939’s The Women, Chaplin’s own The Great Dictator, and other movies all the way into the 1950s before transitioning into TV and pretty much retiring in the early ‘60s.

The Great Dictator (1940)

Chaplin speaks and does double-duty as both a dictator and a poor Jewish barber. This film, a satire on Hitler via a mistaken-identity plot, marks a shift for Chaplin. First of all, gone for good is The Tramp. Second, this is Chaplin’s first talkie, so his humor comes not just from his usual physical antics, but from dialogue, also. At 125 minutes, it was, by far, Chaplin’s longest film up to this point. While his films have often included social commentary and his 1918 short film (or first feature, depending on who you ask) Shoulder Arms touched on war themes, The Great Dictator is less about the laughs and more about a specific target of satire. In a way, Chaplin saw a tyrant who needed to be knocked down a peg. Bear in mind, Chaplin, like the rest of the world, had no idea of the horrors nor the length of inhumanity Hitler and his army had gone during their march towards continental domination. Chaplin later ruminated that he might not have made The Great Dictator had he known what was going on in the concentration camps. Be that as it may, The Great Dictator is a bold and amusing film, a skewering of an international bully of sorts. But it’s a bit less hysterical than his previous works. Save for a few scuffles between the Jewish barber and Nazi soldiers where all parties involved get bonked on the head by a female ally (the wonderful Paulette Goddard again), there are few of the laugh-out-loud sequences in The Great Dictator that Chaplin was known for. The film mostly operates on a light, amusing sort of tone. And, I believe, it is the first of his films to end with a speech by its Every Man protagonist, preaching to its audience messages of peace and taking responsibility for humanity’s future. It is a compelling piece of writing. But may not work for those who resist being lectured.

Overall, The Great Dictator is a bold film of its time. Not many films at that time thumbed their noses at foreign leaders - or any political leader, for that matter. Fritz Lang, who would later emigrate from Germany, made the 1933 film, The Testament of Dr. Mabuse, which took aim at a pre-Chancellor Adolf Hitler. The Three Stooges had a short film, You Natzy Spy!, a few months before The Great Dictator’s release. Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, while not a satire, a spiritual cousin to The Great Dictator in that an average person tries to make change from within the system, spoke out against corrupt politicians in 1939. Citizen Kane would act as allegory for a corrupt media magnate in 1942. The film was released over a year after the beginning of World War II and would be one of the most popular films of 1940 throughout the world.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

The Chaplin of old is officially gone. Over a decade after Modern Times, Chaplin had moved on creatively to different territory with a character that bares no resemblance to his signature character. Here he plays a serial killer… sort of. Monsieur Verdoux is a former banker who felt wronged by his Depression-era termination and has turned towards killing well-to-do women for their money. The idea here is to Have by any means so as to build a better life. Of course, there’s no way Chaplin could play a cold-blooded killer a la Paul Muni’s Scarface. So, Monsieur Verdoux, like The Great Dictator, plays its material with a light tone. Consider it a dark comedy. It is one of the more amusing movies about a serial killer. The humor derives from both a winking attitude by Chaplin and some situational comedy, as when Verdoux attempts to poison one of his marks and the glasses get switched accidentally or when Verdoux’s multiple lives collide at a wedding, causing him to find excuses to hide from one of his marks. Chaplin, again, ends his film with a lecture to his audience. In this, it comes from a murderer and feels a bit dubious compared to the “persecuted Jew posing as Dictator”. By this time, Chaplin’s reputation had been scathed by a paternity scandal, communist claims, and the optics of his marriage to then-18 year-old Oona O’Neill (his last wife). It was a commercial failure in the States and a success in Europe. Chaplin would claim Monsieur Verdoux as his most brilliant film. It may not be, but it is one of Chaplin’s last movies of note and admirable for the risks Chaplin took with it.

Limelight (1952)

Chaplin plays a former vaudeville performer past his prime who tends to a suicidal aspiring ballet dancer (Claire Bloom) in Chaplin’s greatest sound film. While The Great Dictator is bold and pleas to the audience’s humanity while skewering Hitler, Limelight is more reflective and feels like a climax to a legendary career. Yes, Chaplin would go on to make two more film in the following 15 years. But you have Chaplin, through his character, giving advice to a younger generation of entertainers (via Bloom’s dancer) and sharing his thoughts on his career and philosophy on life. It’s also beautifully acted by both Chaplin and Bloom. Bloom was the latest in a long line of ingenues for Chaplin. Limelight was a breakout film for her and, unlike some of Chaplin’s other leading ladies, she would go on to a career that would include The Haunting, Charly, Clash of the Titans, Crimes and Misdemeanors, The King’s Speech and continues today.

Aside from its performances, Limelight also has one of Chaplin’s most beautiful scores. And the film treats us to a finale that features Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton performing together! The film, in part thanks to a 6-minute ballet fantasia - a trend in film at the time that would especially be seen in Gene Kelly musicals - clocks in at 137 minutes, his longest feature for sure. Chaplin would live for another 25 years. But Limelight is a late-career high point and among his greatest films.

A King in New York (1957)

This film, in which Chaplin plays a king who flees his country during a revolution to New York City, is Chaplin’s last starring role. It is also his most scattershot. During the course of 100 minutes, Chaplin takes aim at everything from TV commercials to plastic surgery. His primary target seems to be the aggressive and paranoid nature of its government during the Cold War, as there is much to do about communism and McCarthyism. If one were to isolate each episode of the first and second acts, one would find amusing satires of TV commercials of the time, Rock and Roll, American cinema, and (albeit less so) plastic surgery. But as part of a greater whole that takes on an entirely different subject for the second hour, it all makes A King in New York a far cry from his sharper comedies 20+ years before; the whole thing lacks the impact Chaplin was known for. And that might be why this is one Chaplin’s least-mentioned films. It is, by no means , a bad film. It even recalls The Kid in how a youth, who represents the political voice of the future in this case, is chewed up and spit out by the system. And Chaplin, himself as the King, speaks fondly as an outsider of the country and its possibilities. That is made more interesting when you realize the FBI kicked Chaplin out of the country five years beforehand. But none of it coalesces into a satisfying whole. It remains a curiosity, notable primarily for its extra-textural aspects more than its creative merits.

A Countess From Hong Kong (1967)

Marlon Brando. Sophia Loren. Even Charlie Chaplin pops by (literally!). And yet… this film is a chore. The premise is an Ambassador is stuck in a ship on the way to New York with a Russian stowaway (Sophia Loren). The ‘60s were an odd decade for Marlon Brando, full of lesser-known work that is considered mediocre and forgettable. A Countess from Hong Kong is, regrettably, no exception, despite being written and directed by Chaplin. I guess there’s a reason Brando was not known for his comedic work. Still, Brando was one of the greatest actors of an entire era, starring with one of the greatest international stars to emerge during the ‘60s, Loren. The writing, unfortunately, is the issue here. The premise is simple. The stakes are minimal. The entire movie hangs on whether or not Loren’s character gets caught. But, despite a number of slammed doors and running around, nobody involved can create any spark or excitement in the whole affair. It’s absolutely remarkable how dull the entire thing can be despite such extraordinary talent involved. There is some mild delight in seeing Sydney and Geraldine Chaplin, Charlie’s brother and daughter, respectively. Despite a lot of reading and retrospectives, I’d never heard of A Countess from Hong Kong until endeavoring on this article. It is virtually forgotten and, unfortunately, not a gem.

The Ranking

On Instagram, Followers voted The Circus their 2nd favorite movie of the Silent Era. Modern Times was their favorite movie of the 1930s. The Great Dictator was their 4th favorite movie of the ‘40s. Limelight fared less well when included in a poll for ‘50s movies, being completely shut out in the first round. Here, however, is my ranking of Charlie Chaplin’s full-length feature films from best to worst:

Modern Times

City Lights

The Circus

Limelight

The Great Dictator

The Kid

The Gold Rush

Monsieur Verdoux

A King in New York

A Countess from Hong Kong

What are your thoughts? Which do you think is Chaplin’s best full-length feature? Which is your favorite?